People have long taken pleasure in adding some element of individual expression to the media they use to read. This is apparent nearly everywhere on the computers and websites we use daily to access news, scholarship, social updates and more. We customize our cover photos and profile pictures on sites like Facebook, adorn our laptop screens with “wallpaper, and choose artistic, blingy, or ironic covers to enclose our phones. These are all not only statements intended to convey something about who we are to the people around us, but also serve as reminders to ourselves that we have something unique to contribute to the world every time we turn to read an online article or a text from a friend. This universal desire to combine individual expression with the experience of reading and viewing material was the basis for a recen

t catchy MacBook ad in which a rapid succession of images shows the iconic apple logo on the case of a laptop adorned by various customized stickers, from hipster hats to Homer Simpson: https://youtu.be/5SIgYp3XTMk The ad is selling a product intended to act as a person’s gateway to the world’s information, and plays upon the concurrent need for the object offering that experience to give people an experience in common together, suggested by the apple logo that unites all MacBook owners as a group, while at the same time providing a distinctly personal experience, expressed by the imaginative stickers.

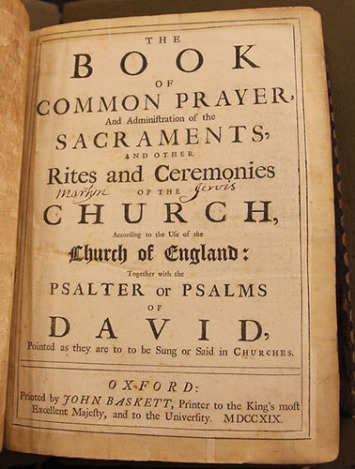

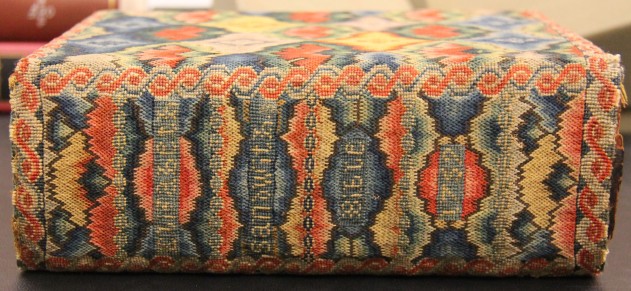

The image at the top of today’s blog post is, in many ways, an 18th century equivalent of our Facebook cover images and digital wallpaper. It shows the spine of an embroidered binding covering a Book of Common Prayer bound with a Bible. The book is located at the Library Company of Philadelphia (Am 1719 Eng Al 99 no. 218), but owned by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Their collection boasts a rich range of material from documents related to regional and family histories from the 18th century to the present, to nationally important historical documents such as the first draft of the United States Constitution. Several images from books owned by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and located at the Library Company have recently been added to POP. The title page of the book is like many other devotional 18th century printed texts of the period:

A reader turning to it would receive the sort of message appropriate to the work it contains, a book of common prayer intended to be a reading experience in common between the pious reader and her social group. Seemingly numberless 18th century households would have contained a similar bible or prayer book. However, this particular copy of a universalizing text has not only been adorned with the inscription of a past owner named Martyn Jervis but has, more spectacularly, been wrapped in the brilliant colors of a distinctly personal creation. From across a room the beautifully preserved colors, worked in worsted wool in a a bold, flame stitch pattern, make an immediate statement that this is a book that was owned by someone with something to show the world.

A reader turning to it would receive the sort of message appropriate to the work it contains, a book of common prayer intended to be a reading experience in common between the pious reader and her social group. Seemingly numberless 18th century households would have contained a similar bible or prayer book. However, this particular copy of a universalizing text has not only been adorned with the inscription of a past owner named Martyn Jervis but has, more spectacularly, been wrapped in the brilliant colors of a distinctly personal creation. From across a room the beautifully preserved colors, worked in worsted wool in a a bold, flame stitch pattern, make an immediate statement that this is a book that was owned by someone with something to show the world.

View on the POP Flickr feed

View on the POP Flickr feed

A closer examination of the spine reveals a hand stitched provenance mark showing the name, Elizabeth Sandwith, and the date, 1759.

The owner, Elizabeth Sandwith, is better known by her married name, Elizabeth Drinker, and was a notable member of the early American Quaker community. Her diary, which is also a part of the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (Collection 1760), is a well known document of the experience of a Quaker woman in the revolutionary era. It also contains a specific reference to this book. In an entry dated January 15, 1759, when she was 24 years old, she writes: “Stayed home all day. Began to work a large worsted bible cover.” This brief note of the moment in time when Drinker (then Sandwith) began stitching the colorful book cover reinforces the sense, already evoked by the stitching itself, of the human fingers that crafted the pattern to show the world some glimmer of the human mind that read the prayers and verses printed in the pages between the covers. This embroidery work, taken up by a woman in a quiet moment at home 256 years ago, today serves as a reminder to us that all we put our names to, all we add of our own selves to the world, and all the ways what we read, view, and watch are wrapped in the colors of our own individual experience.

Rivals the author’s own talent in stitchery.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This blog could use some professional proof-reading or editing. This post, for example, contains numerous grammatical, spelling, and punctuation errors. Also, “numberless” is a strange word choice — there is a number, we just don’t know what it is. Lastly, I believe the book cover was done in needlepoint, not embroidery.

LikeLike

It is true that, lacking a professional editor, this blog relies on its author’s–sometimes late night, sometimes rushed– proof-reading. I do my humble best. “Numberless” was a bit of a poetic license. I’ve amended with “seemingly,” since I do like the added precision.

Your point about needlepoint vs embroidery I find interesting. As an avid practitioner of needlepoint, counted cross-stitch, knitting, and other needle arts, I am aware of the frequent distinction made by the modern stitcher between work designated as “embroidery” and that referred to as “needlepoint.” I employed the term “embroidered binding” in this instance because this is the term used in rare book library catalogs to designate all manner of needlework covers, and because it was my sense as a literary historian that the term has been long employed as a general way of referring to an array of needle craft. The OED tends to confirm this, with its first definition for “embroidered” reading: “Of textile fabrics, leather, etc.: Adorned or variegated with figures of needlework. Also of the needlework itself.” OED citations for this use of the term go back to John Florio in the 16th century. Apparently this was also about the time that what we call “needlepoint” arose, according to the OED citation under the entry for “needlepoint” from a 1973 book on embroidery that reads: “It was some time during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that embroidery on canvas, or needlepoint as we know it today, began to develop.” I would be interested, however, to know the history of how the use of “embroidery” to refer to a precise form of needlework, distinct from needlepoint, came about.

Do you needlepoint yourself?

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is the first time I’ve seen “needlepoint” verbified. Perhaps I have lived a sheltered life.

LikeLike

Despite the comments from DC (and I loved your response), I found this column to be delightful and informative. As one who also does multiple forms of needlework I always appreciate it when someone takes the time to observe and comment on the topic. Elizabeth used her art skills to enrich her daily life and to create more beauty around her. Much better engagement of time than viewing cat videos on Facebook.

LikeLike

Thanks. I’m glad you enjoyed Elizabeth’s binding, and also glad that 18th century needlework can provide a little interlude to the enjoyment of cat videos. Though, I must confess to indulging in the medieval equivalent of the cat video in a few of the features on the “Book Animations” page of this blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: #187 | The Alipore Post